Chinese

police attack Japanese press in custody

AFP AND AP, BEIJING AND KASHGAR, CHINA

Wednesday, Aug 06, 2008, Page 1

Chinese border police apologized yesterday for their treatment of two Japanese

reporters covering a deadly assault in the northwest of the country, state media

said.

The apology came after the border police “clashed” with the Japanese reporters,

who had arrived in Xinjiang Province after an attack there on Monday left 16

police officers dead, according to Xinhua.

A photographer for the Tokyo Shimbun newspaper was forcibly detained late on

Monday in the city of Kashgar, his employer said.

A reporter for the Nippon Television Network was also detained and manhandled by

Chinese police who pushed his face to the ground, the network said.

Masami Kawakita, 38, was detained “and then kicked by police,” said a Tokyo

Shimbun spokesman. “He was released two hours later.”

Nippon Television Network said Shinji Katsuta was held for two hours and then

questioned for about an hour at his hotel, describing the incident as “extremely

deplorable.”

The network received word that local police had requested a meeting to apologize

for the incident, a spokesman said.

“We heard that the Chinese side pointed out that it is forbidden to film

military facilities, and it seems like there was confusion because the scene of

the assault was just 50m from a military facility,” he said.

Security checks on roads and public buses were stepped up in Xinjiang yesterday

with Xinhua reporting that authorities had reinforced the police presence on

roads leading into Kashgar and ordered a full security alert in public places,

including government office buildings, schools and hospitals. Police boarded

vehicles at checkpoints to search passengers’ bags, Xinhua said.

Meanwhile, a 6.0-magnitude earthquake hit Sichuan Province yesterday, near the

area devastated by a quake earlier this year, the US Geological Survey said.

An official with China Earthquake Administration confirmed that an “aftershock”

hit the area.

“So far, we have not received any report of casualties,” he said.

Xinhua said the quake was felt in the Sichuan capital Chengdu. The Olympic torch

relay passed through Chengdu yesterday, its last leg before reaching Beijing.

|

|

| FEEDING TIME A Muller's Barbet feeds its two chicks in a hole in a tree outside the emergency room of the National Taiwan University Hospital in downtown Taipei.

|

No more

'mutual' goodwill, please

Wednesday, Aug 06, 2008, Page 8

When Beijing's hegemonic epithet for Taiwan's Olympic team made an unwelcome

reappearance on China Central Television (CCTV) over the weekend, the response

by the Taiwanese government was equally disappointing.

Reporting on taekwondo gold medalist Chu Mu-yen (朱木炎), CCTV again swapped the

nation’s official Olympic name for Zhongguo Taibei. An apology from Beijing

seems unlikely, however, judging from the Presidential Office’s timid statement

on Sunday.

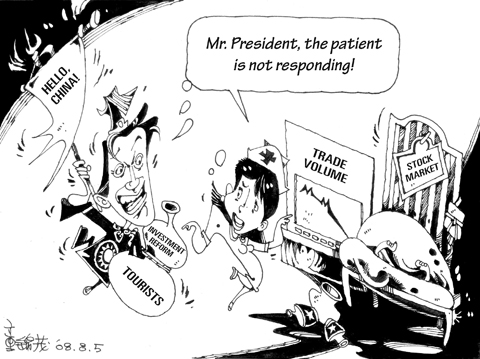

The re-emergence of this contrived moniker was bad news for President Ma Ying-jeou

(馬英九), who only a week earlier said that China had agreed to end its name game

and so declared a diplomatic victory for his administration. For Ma, Beijing’s

about-face was a scarce and sorely needed gesture of “goodwill” to combat

critics at home who have said cross-strait “compromise” is a one-way street.

That may be why the office was reluctant to raise its voice over CCTV’s recent

decision to keep using the non-official title, lest it erase the earlier

triumph. Instead, the Presidential Office said it would monitor the situation,

adding that CCTV had reportedly admitted to a “technical error.”

The government is not alone in its reluctance to react. Chinese Nationalist

Party (KMT) Chairman Wu Poh-hsiung (吳伯雄), who last month bristled at the name

change, is now strangely quiet. Wu had said he would cancel his trip to attend

the Olympics if China continued to play “word games.”

But choosing not to issue an immediate protest this time was a risky tactic for

Ma. The administration’s stern objection to altering Taiwan’s Olympic name was

as important for the president’s image at home as it was for building trust with

Beijing. Silence on the issue now could be interpreted as spinelessness, further

compromising the nation’s bargaining position with China and eroding Ma’s

already sagging approval ratings.

The timing was also awkward for Ma, who, on the same day as the Presidential

Office’s ineffectual response to CCTV, touted his administration’s diplomatic

prowess to a group of former foreign ministers. At a dinner honoring the

officials, Ma sung the praises of agreeing to disagree, saying that his modus

vivendi approach to foreign policy had already paid off.

But there is cause to object to this recurring theme. When Beijing’s Taiwan

Affairs Office first dreamed up Zhongguo Taibei, Legislative Speaker Wang Jin-pyng

(王金平), after meeting with the president and premier, called on China to remember

its consensus with Taiwan to set aside disputes. Unfortunately, there is scant

evidence that Beijing sees itself as having reached any such deal. Instead,

China seems more interested in testing the waters to see just how eager the new

government is to maintain a show of “mutual goodwill.”

On Sunday, Ma said his “practical” approach would “protect the interests of the

Republic of China” and “restore mutual trust” with other governments. The

strategy had already improved relations with China as well as with allied

nations, he said.

The sum of Ma’s many conciliatory remarks, however, has not put a stop to

Beijing’s encroachment on Taiwan’s identity and international space. In that

context, soft reactions to provocations like CCTV’s “error” may be setting the

nation up for a hard fall when it becomes clear that Beijing was never

interested in agreeing to disagree.

Stop

criticizing China — they've come so far

China celebrated when it won

the Olympics, sensing a chance to show its true self, but all it receives are

Western attacks

By Lijia Zhang

THE OBSERVER, BEIJING

Wednesday, Aug 06, 2008, Page 9

'With only a few days to go before the opening ceremony, Beijing, having undergone a facelift, has never been so beautiful, clean and quiet.'

When I was at school, sports lessons included an exercise

where we threw hand grenades (made from wood topped with metal to resemble the

real thing) against a wall over which a red slogan had been stretched offering

the reason for such a militaristic pastime: “Exercise our bodies and protect our

motherland.”

We feared that China might be invaded one day by the American “imperialists” or

Soviet “revisionists.” Indeed, the whole West held evil intent towards us.

Living in a closed country, we had little idea about the outside world.

I went to school in Nanjing in the early 1970s, when the revolutionary fever of

the Cultural Revolution was calming down. A few years earlier, my father had

been banished to the countryside for criticizing the government. My grandfather,

a small-time grain dealer, had committed suicide, as he worried his

not-so-politically-correct background would land him in trouble.

These were the darkest of times for my family, as well as for our nation. China

has come a long way since then, yet the image of those dark days remains deeply

imprinted on Western minds. I wonder whether the West is a little too keen to

report the negative stories. Or perhaps the West feels more comfortable hearing

such stories?

That’s my impression, as a Chinese who has lived abroad, but has returned to

Beijing. Even during those days throwing grenades, I dreamt of becoming a

journalist and writer. That dream was shattered when I was 16 and my mother

dragged me to work at a state-owned missile factory.

My journalistic career started with the Olympics. In 1993, on the night when the

result of the first bid was announced, I was at Tiananmen Square. I recall the

fountain going off as we thought China had won the bid. It was heartbreaking to

interview the bitterly disappointed crowds. But, in truth, China wasn’t really

ready. The memory of the bloody crackdown in 1989 was still fresh.

I was also in Beijing eight years later when China did win the bid. In our

neighborhood, grannies spent the whole afternoon practicing their dance steps

and their husbands beat drums and gongs. This time, we were not disappointed.

The wild celebration, the deafening noise of firecrackers, laughter and ecstatic

cries went on the whole night. I was interviewed by the BBC.

I said: “In the ecstatic cries, I heard Chinese people’s longing for the

recognition and respect from the world.”

I was just as happy as everyone else. Ever since the economic reforms, China has

lifted millions of people out of poverty — an incredible feat. As a child, I

used to roast cicadas to satisfy my craving for meat; now my 19-year-old nephew,

a student in Nanjing, drives his own car. People are enjoying a great deal more

personal freedom. As a girl in the rocket factory, I had to endure so many

rules. I worked there for 10 years. I was never promoted, partly because of my

naturally curly hair — my boss thought I wore a perm. Back then, only those with

a bourgeois outlook would curl their hair. These days, young women curl their

hair, shave off their hair or change the colors of their hair whenever they

want. It’s not a small thing.

Over the past few years, I have seen how the capital has been transformed.

State-of-the-art buildings — not just Olympic buildings such as the Bird’s Nest

and the Water Cube — have popped up like mushrooms after a spring rain. With

only a few days to go before the opening ceremony, Beijing, having undergone a

facelift, has never been so beautiful, clean and quiet.

Huge efforts and sacrifices have been made. To ensure the best possible air

quality, polluting factories around Beijing have been shut down, construction

work has been halted and cars have been taken off the roads (the results,

admittedly, have been mixed). Other measures are excessive: beggars, the

homeless and migrants without documents have been driven out. Petitioners who

bring their grievances to the Supreme People’s Court have been stopped from

entering the capital. Potential troublemakers are being monitored or are under

house arrest. Such has been the stance the authorities adopt while dealing with

uncertainly.

Yet Beijing’s Olympics will be a success because the majority of the population

wants them to be, not just because the government wants to use Olympic success

to gain legitimacy. Xia Fengzhi, a 67-year-old retired worker and a volunteer,

told me how happy and excited he is about the Games.

“I want foreigners to see what China has achieved. We were called the ‘sick man

of Asia.’ Now we are strong and rich enough to hold such a major international

event,” he said.

No doubt there will be many more negative stories abroad, criticizing China’s

human rights abuses, the lack of media freedom and the over-tight security. Of

course, some Chinese have no access to the reports, but those who do tend to

dismiss them as grumbles from anti-China forces. In a survey conducted by the

Pew Research Center, China’s people ranked first among 24 nations in their

optimism about their country’s future, buoyed by the fast economic growth and

the promise of the Olympics.

There is, I believe, another factor — the timing. The survey was conducted this

spring, just after the unrest in Tibet and during the troubled Olympic torch

relay, when China experienced a surge of nationalism in response to what many

Chinese regarded as an “anti-China feeling” in the West and “biased” Tibet

reports.

I have no problem with the negative stories, but I think it’s wrong for the West

to stand in moral judgment, especially when some of the accusations are not

true. For example, what happened in Lhasa, in my view, was far more complicated

than “the Chinese government’s ruthless crackdown on Tibetan protest.” There was

a peaceful protest, but there was also a violent racial riot, one I doubt that

would be tolerated in any Western country.

As a journalist, most of my stories criticize the government, which seems to

have little idea as to how to present itself. Blessed with such domestic support

and armed with skills in mass organization, the authorities could have taken a

more relaxed approach to this festival of sport. Why didn’t it make the Olympic

Games a fun event — China’s big coming-out party? It didn’t need to cause so

much interruption to people’s lives. It would have been far better to let the

world to see China as it actually is.

I can’t help feeling there’s been a missed opportunity on more important

matters, too. Our leaders could have made use of this to address the real

issues: cracking down on corruption, improving the rule of law, relaxing media

control and opening the country further.

But don’t doubt our support for the Beijing Games. The Olympics are meant to be

an occasion to bring different people with different views together. It’ll

provide a chance for China and the rest of the world to understand each other.

Although I can understand how China’s undemocratic political system and lack of

transparency make the West uneasy, especially when matched with the country’s

rise, much of the fear is generated by ignorance.

Today’s schoolchildren enjoy far more sophisticated sports than throwing hand

grenades. They know a lot more about the outside world. I wonder if Western

children know as much about China? And if they did, would there be still be the

same fear? Maybe the Olympics will bring us closer.

Lijia Zhang is the author of “Socialism

Is Great!”: A Worker’s Memoir of the New China.