|

Former political prisoners recall

friendship, hardship

By Loa Iok-sin

STAFF REPORTER

Monday, May 24, 2010, Page 3

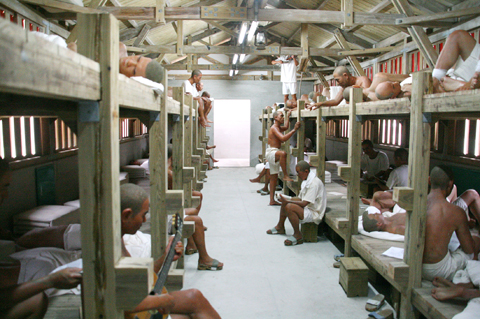

Wax figures recreate a scene inside the

dormitory of the New Life Correction Center on Green Island on May 15.

PHOTO: LOA IOK-SIN, TAIPEI TIMES

Communist or Taiwan independence advocate; Taiwan native or

mainlander.

It didn’t matter. If the authoritarian government of dictator Chiang Kai-shek

(蔣介石) believed you were a dissident, you could be locked up for decades or even

executed.

“We’re good buddies, we’re brothers,” 84-year-old Huang Kuang-hai (黃廣海) said,

putting his arm around 85-year-old Kue Chin-sun (郭振純), both of them smiling.

The two men — along with dozens of other former political prisoners incarcerated

on Green Island — returned to the island recently, decades after their release

to attend the inauguration of a reconstructed New Life Correction Center

(新生訓導處).

Taiwan was officially under martial law from 1949 until 1987. From the 1950s

thousands of political prisoners were kept first at the New Life Correction

Center and then Oasis Village (綠洲山莊).

While it may seem perfectly normal for two former political prisoners to call

each other friends, the relationship is more surprising when one learns about

their backgrounds.

An original stone house as constructed by

political prisoners in the 1950s is pictured on Green Island on May 15.

PHOTO: LOA IOK-SIN, TAIPEI TIMES

Huang was born in Guangzhou, China, in 1926, and came to Taiwan in 1950 as a

soldier when the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) retreated after losing the

civil war against the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Although he was with KMT

troops, Huang had always been fond of communism and to this date, the

unification of Taiwan and China is still his biggest dream.

On the other hand, Kue is a Taiwan native born in 1925 and a diehard advocate

for Taiwan independence.

“We’re good buddies because we were both jailed for more than 20 years and for

the most part, we were jailed together ... Of course we have different political

views, but political views didn’t really play a role when we lived together,

worked together and helped each other out as political prisoners,” Huang said.

“We knew we disagreed with each other on ideology, so we never talked too much

about it,” he added.

Although Huang was a CCP sympathizer, he never actually participated in any

organization or political activities related to the party.

“I was sentenced to life in prison for complaining about Chiang Kai-shek in

letters to friends in Hong Kong ... In those letters, I complained that Chiang

was a dictator and the KMT regime was an authoritarian one,” he said.

“I was in the military at the time and they always checked what we wrote in

letters — especially if the letters were going abroad — so they decided to

charge me with ‘repeatedly spreading false rumors’ and sentenced me to life in

prison,” he said.

Huang was sent to prison in 1954, and did not get out until 1975 when an amnesty

was declared after Chiang passed away on April 5 that year.

During those 21 years, he was incarcerated in six prisons — two different Taiwan

Garrison Command detention centers in Taipei City; the Ankeng Military Prison

(安坑軍人監獄) in Sindian City (新店), Taipei County; the New Life Correction Center and

the Oasis Village on Green Island and Taiyuan Prison (泰源監獄) in Donghe Township

(東河), Taitung County.

It was at Taiyuan and on Green Island that Huang met Kue.

Although Kue, was one of the many young Taiwanese who took up arms to fight the

KMT following the 228 Incident in 1947, he escaped the mass arrests and

executions that followed. He was less fortunate during the Marital Law Era.

In 1951, Kue campaigned for non-KMT candidate Yeh Ting-kuei (葉廷珪) in his

victorious bid for Tainan City mayor. After the election, someone reported to

the secret service that Yeh was connected to Thomas Liao (廖文毅), a Taiwan

independence movement leader who formed the Provisional Government of the

Republic of Formosa in Japan.

Kue said he was a supporter of Taiwan independence, but did not play a role in

any advocacy organizations.

“They tortured me, trying to get me to admit to things I did not do, but I

refused, so they could only sentence me to life in prison under the charge of

‘repeated participation in unlawful assemblies’ ... If I gave in, I could’ve

been sentenced to death right away,” he said.

Kue said that when he was first arrested in Tainan, the secret service agents

tore the nails off both his thumbs and his toes. He then was put into a big

linen bag and dumped into a river for a few seconds.

“The worst thing was when they spilled sugar water all over me, and threw me

into a courtyard — ants quickly found their way to the sweet taste, and bit me

all over ... My hands had been tied behind me, so I could do nothing but roll on

the ground,” Kue said.

Both Huang and Kue were sent to the New Life Correction Center in the 1950s, and

transferred to Taiyuan Prison in the 1960s. However, the two of them, along with

all other political prisoners, were sent back to the newly constructed Oasis

Village in the 1970s after several pro-independence prisoners, including Kue,

organized a failed uprising.

Kue was also released when an amnesty was declared after Chiang’s death.

Secret reports and torture were probably key reasons behind that high percentage

of political prisoners who were falsely charged.

“During the initial years of the Martial Law Era, you could receive part of a

dissident’s property if you reported on the person and the person was ‘proven’

guilty,” said Tsao Chin-jung (曹欽榮), an independent researcher of political

cases during the Martial Law Era.

“If the accuser wanted the money and the secret service agents needed names to

meet their quota, then they tortured the victims into admitting whatever they

wanted them to,” Tsao said.

While political prisoners were from all walks of life, another researcher who

specializes in mainlander political prisoners, Huang Luo-fei (黃洛斐), said that

Mainlanders were more likely to be reported as communists.

“Most Mainlanders in Taiwan had families and friends in China and they would

miss their hometowns and their loved ones ... Well, a letter sent back home, a

complaint about the KMT or saying that he or she wanted to go home could often

be cited as evidence of a ‘connection to the communist bandits,’” Huang said.

According to an estimate from the Compensation Foundation for Victims of

Improper Verdicts in the Martial Law Era (財團法人戒嚴時期不當叛亂暨匪諜審判案件補償基金會), more than

90 percent of political prisoners during the Martial Law period were unaware of

the accusations made against them.

To date, the foundation has identified around 9,000 political victims from that

time,

“But the real number is much higher because many government agencies in charge

of handling political prisoners are still either unwilling to publicize lists or

have already destroyed them,” a foundation board member, Chiu Rong-jeo (邱榮舉),

told the Taipei Times.

“The Martial Law Era has a legacy that still impacts our society today ... For

example, the culture of reporting on someone and the mentality of being overly

careful in all things to avoid getting into trouble — especially in the

government system,” Tsao said.

Issues that still need to be addressed are the unwillingness of public servants

and officials who collaborated with the authoritarian regime to publicize all

the official records of that period and the continued glorification of Chiang

Kai-shek, Tsao said.

|

![]()

![]()

![]()