¡@

¡@

Taiwan and fear in US-China ties

By Joseph S. Nye

Monday, Jan 14, 2008, Page 8

Opinion polls indicate that one-third of Americans believe that China will "soon

dominate the world," while nearly half view China's emergence as a "threat to

world peace." In turn, many Chinese fear that the US will not accept their

"peaceful rise." Americans and Chinese must avoid such exaggerated fears.

Maintaining good US-China relations will be a key determinant of global

stability in this century.

Perhaps the greatest threat to the bilateral relationship is the belief that

conflict is inevitable. Throughout history, whenever a rising power creates fear

among its neighbors and other great powers, that fear becomes a cause of

conflict. In such circumstances, seemingly small events can trigger an

unforeseen and disastrous chain reaction.

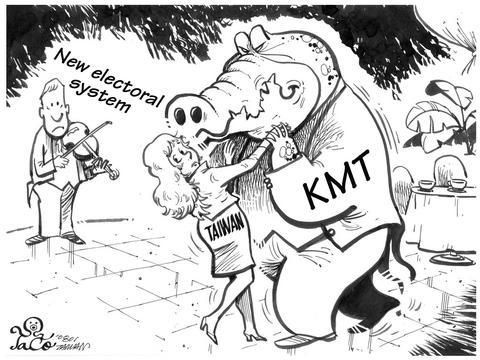

Today, the greatest prospect of a destabilizing incident lies in the Taiwan

Strait.

The US does not challenge China's sovereignty over Taiwan, but it wants a

peaceful settlement that will maintain Taiwan's democratic institutions. In

Taiwan, there is a growing sense of national identity, but a sharp division

between pragmatists of the pan-blue alliance, who realize that geography will

require a compromise with the mainland, and the ruling pan-green alliance, which

aspires in varying degrees to achieve independence.

Some observers fear that President Chen Shui-bian (³¯¤ô«ó) will seek a pretext to

prevent defeat in March's presidential elections. He is advocating a referendum

on whether Taiwan should join the UN, which China views as provocative. Chen has

replied that it is China "that is acting provocatively today."

Washington is concerned. US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice told reporters

that "we think that Taiwan's referendum to apply to the UN under the name

`Taiwan' is a provocative policy. It unnecessarily raises tensions in the Taiwan

Strait and it promises no real benefits for the people of Taiwan on the

international stage."

She also reiterated the administration policy opposing unilateral threats by

either side that change the status quo.

The same day, US Secretary of Defense Robert Gates criticized China for

curtailing US naval visits to China over arms sales to Taiwan. Gates said he

told the Chinese that the sales were consistent with past policy and that "as

long as they continued to build up their forces on their side of the Taiwan

Strait, we would continue to give Taiwan the resources necessary to defend

itself."

Gates added, however, that despite China's rising defense budget, "I don't

consider China an enemy, and I think there are opportunities for continued

cooperation in a number of areas."

In principle, cross-strait tensions need not lead to conflict. With increasing

change in China and growing economic and social contacts across the Strait, it

should be possible to find a formula that allows the Taiwanese to maintain their

market economy and democratic system without a placard at the UN.

The US has tried to allow for this evolution by stressing two themes: no

independence for Taiwan and no use of force by China. But given the danger that

could grow out of political competition in Taiwan or impatience in the People's

Liberation Army, the US would be wise to encourage more active contacts and

negotiations between the two sides.

The US has a broad national interest in maintaining good relations with China,

as well as a specific human rights interest in protecting Taiwan's democracy.

But the US does not have a national interest in helping Taiwan become a

sovereign country with a seat at the UN, and efforts by some Taiwanese to do so

present the greatest danger of a miscalculation that could create enmity between

the US and China. Some Chinese already suspect the US of seeking an independent

Taiwan as an "unsinkable aircraft carrier" against a future Chinese enemy. They

are wrong, but such suspicions can feed a climate of enmity.

If the US treats China as an enemy, it will ensure future enmity. While we

cannot be sure how China will evolve, it makes no sense to foreclose the

prospect of a better future. Washington's policy combines economic integration

with a hedge against future uncertainty.

The US-Japan security alliance means China cannot play a "Japan card." But while

such hedging is natural in world politics, modesty is important for both sides.

If the overall climate is one of distrust, what looks like a hedge to one side

can look like a threat to the other.

There is no need for the US and China to go to war. Both must take care that an

incident over Taiwan does not lead in that direction, and avoid letting

exaggerated fears create a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Joseph S. Nye is a professor at Harvard

University.

¡@

¡@

|

|

|

FLOWER SHOW |

¡@