Despite

mistakes, friends defend Chiou’s integrity

By Shih Hsiu-Chuan

STAFF REPORTER

Monday, May 12, 2008, Page 3

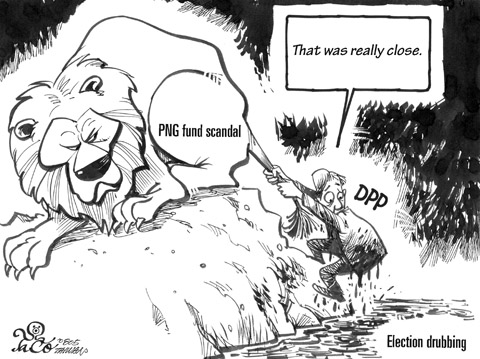

Described by his many friends as a man who knows nothing but politics, former

vice premier Chiou I-jen (邱義仁) made a painful decision last week when he offered

to leave his “beloved” Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and retire from

politics for good to take responsibility following a diplomatic scandal.

“When I walk out of the Executive Yuan today, I will no longer be involved in

politics. Everyone more or less knows how this makes me feel,” Chiou said when

asked about his state of mind as he resigned on May 6.

Kaohsiung City Mayor Chen Chu (陳菊), who steered Chiou into politics by

encouraging him to campaign for the late dangwai democracy activist Kuo Yu-hsin

(郭雨新) in 1975, said: “For Chiou, quitting politics and the DPP is the severest

punishment.”

Chiou’s resignation came after a secretive deal involving two shady brokers and

US$30 million in funds intended for the establishment of diplomatic relations

with Papua New Guinea was botched, resulting in the disappearance of the funds

from a Singapore bank account.

Chiou, in his former position as head of the National Security Council (NSC),

was the instigator of the deal, which also led former vice minister of national

defense Ko Cheng-heng (柯承亨) and former minister of foreign affairs James Huang

(黃志芳) to resign in disgrace.

Some opposition lawmakers have alleged that the affair was in reality “a money

laundering scheme in the guise of a diplomatic deal” set up by Chiou.

Those accusations were made on the basis of a sequence of mistakes such as

Chiou’s failure to request background and reliability checks by security

agencies on the two brokers, as well as Huang’s ministry bypassing regular

procedures for the appropriation of funds.

“Having middlemen involved in efforts to develop diplomatic ties is unavoidable,

but [officials] cannot act on trust alone,” former minister of foreign affairs

Chen Chien-jen (程建人) said.

Loh I-cheng (陸以正), a retired diplomat, said he did not understand how the

Ministry of Foreign Affairs could have remitted the money to a joint account

rather than open an escrow account with all payments contingent on the

establishment of relations between the two countries.

“The ministry might just as well have had one of its officials participate in

the joint account,” Loh said.

All the irregularities, added to the fact that the country’s highest

intelligence agency managed to get fooled by two brokers — whose shady past was

no secret — made the story difficult to believe for Chiou’s opponents.

However, Chiou’s DPP allies, who gave him the sobriquet Laba — a Hoklo term

meaning “trumpet,” quickly came to his defense.

Chiou earned that nickname during the dangwai era, as what he thought and said

about things was always accepted by groups, which underscored his influence in

the DPP.

But as Chen Chu said, Chiou’s friends believe the scandal was the result of

Chiou’s “mistaken judgment” on the two brokers as well as his arm’s length

decision-making style, in which he only oversees things from a general

perspective and lets his subordinates work out the details.

“The thing about Chiou Laba, is that he loves power, but he has never shown an

interest in money since I have known him,” aid Chen Chun-lin (陳俊麟), vice

chairman of the Executive Yuan’s Research, Development and Evaluation

Commission.

Chen Chun-lin, a member of the DPP’s disbanded New Tide faction, of which Chiou

was a founder, said: “Chiou Laba knows he is smart enough. He has confidence in

his capabilities and he wants to hold political power so that he can get things

done.”

Chiou’s talent for politics, added to the “philosophy of being

second-in-command,” to which he has subscribed throughout his political life,

made him the best choice for secretary-general.

Having served as the party’s secretary-general under former chairmen Shih Ming-teh

(施明德), Hsu Hsin-liang (�?}) and Lin I-hsiung (林義雄) while the party was in

opposition and then as secretary-general for the Cabinet, the Presidential

Office and the NSC after the DPP came to power in 2000, Chiou was referred to as

a “permanent secretary-general.”

However, Chiou’s shrewdness in politics stood in clear contrast to his

incompetence in handling real-life affairs.

Chen Chun-lin said Chiou is like a “retarded child” when it comes to his life.

“[Chiou] eats instant noodles and microwave food when he is at home. He is a

half-idiot when it comes to computers, knowing only how to surf the Internet. I

believe he doesn’t even know how to send text messages and has no idea about

‘what a joint account is,’” Chen Chun-lin said.

He was refereeing to remarks Chiou made recently while seeking to clarify media

reports that he had sent text messages to Ching and ordered Huang to remit the

money to the joint account.

“Chiou Laba never pursues material comforts. He just has enough to get by. If he

has anything of value, it would probably be his pen collection,” Chen Chun-lin

said.

Chen Chun-lin said Chiou spends most of his spare time listening to “Beatles-era

rock-and-roll” and watching “old movies,” activities Chiou has regaled in since

his student years at National Taiwan University’s department of philosophy.

But when 13 teachers from the department lost their jobs for criticizing the

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) regime in early 1970s, Chiou switched his

graduate-school major to politics.

KMT Legislator John Chiang (蔣孝嚴) said the Papua New Guinea scandal was likely

the result of the DPP government’s “continued mistrust of professional

diplomats,” referring to diplomatic personnel educated and trained before the

DPP came into power.

The fact that the country’s representative office in Singapore was totally

excluded from participating in the PNG case, Chiang said, highlighted that

distrust.

DPP Department of International Affairs Director Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) disagreed,

saying that “Chiou would not have passed the PNG case to the ministry if such

mistrust had existed.”

Hsiao said that “making inquiries about executive details is not Laba’s ways of

doing things,” based on which she believed Huang’s ministry had received the

appropriate authorizations by Chiou.

“Laba made some mistakes: He trusted [Ching and Wu] too easily. Only a few

people were in the loop and he didn’t consult others. But, oftentimes, such

behavior is crucial in handling confidential diplomacy,” Hsiao said.

“On a couple of occasions before, we weren’t able to pursue confidential

diplomatic projects after news of our efforts had somehow leaked. It’s an

unfortunate situation for Taiwan,” Hsiao said, recalling similar cases during

her time in the presidential office.

The PNG case has heavily tarnished the image of the DPP, the government and the

country, for which Chiou should take responsibility, Hsiao said. But Chiou’s

“integrity” is not questioned by people who know him well, even though the whole

matter has yet to be cleared up, she said.

The

pitfalls of the unaccountable

By J. Michael Cole

寇謚將

Monday, May 12, 2008, Page 8

Special advisers are a proliferating breed, roaming the planet with their

suitcases and delivering on issues as varied as nuclear disarmament in North

Korea, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and oil deals in the Caspian. In many

instances, these individuals — former officials, academics and sometimes

cultural icons — bring specific qualifications or moral weight to the table,

which the governments that dispatch them hope will increase their chances of

obtaining what they want.

What all these track-II diplomats have in common, however, is that they are not

elected, which means that they are often unaccountable and, in many instances,

are paid sums of money well beyond the limits set for public servants.

In addition, far too often special advisers are drawn from a pool of politically

connected individuals or appointed by politicians more as a reward for past

deeds or allegiance than for their qualifications. In other words, the lack of

supervision and regulation surrounding the appointment of special advisers

invites corruption and means that under certain circumstances the narrow

interests of a select group rather than those of the country are served.

Such arguments may have surfaced — and no one could have questioned their

validity — as the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) essentially blocked President

Chen Shui-bian’s (陳水扁) budget for special advisers, leading the Democratic

Progressive Party (DPP) government to abandon its reliance on such individuals

in 2006.

Two years later, president-elect Ma Ying-jeou’s (馬英九) victory in the March

election was partly the result of his advocacy of a “cleaner” government, which

seemed to dovetail with the KMT’s opposition to the DPP’s use of special

advisers.

But in a reversal of position, the KMT is now proposing to resurrect the budget

for special advisers, which shows yet again that the party’s opposition to DPP

practices over the past eight years was more cynical political maneuvering than

a concerted effort to better serve the people of Taiwan.

Furthermore, given the party’s history (and the jury is still out on whether it

has reformed itself), there exists a very real possibility that in the coming

months the budget set aside for such positions will grow and that the

attributions of an already less-than-transparent system will become even more

opaque.

For a party with a long tradition of kickbacks, special advisers only represent

one among many means by which to line the pockets of supporters and cronies, or

win new allegiances.

Even more worrying, perhaps, is that the appointment of special advisers under a

KMT government would be the continuation of a practice, honed in the past eight

years, of conducting diplomacy via unofficial channels, which translates into

sets of decisions that, while they can potentially affect the entire nation, are

made by unelected officials (former KMT chairman Lien Chan [連戰] comes to mind)

in backroom deals that have more in common with black-market barter than

state-to-state diplomacy.

Moreover, as the Ma administration has made some concessions to the opposition

by bringing into its Cabinet non-KMT candidates, special advisers could provide

the means to work outside the veneer of multiplicity by conducting real

diplomacy via back channels, thus nullifying the ability of non-KMT Cabinet

members to effect change and balance out a stacked executive and legislature.

There is nothing intrinsically wrong with track-II diplomacy, as long as the

special advisers who engage in it operate within well-established and enforced

boundaries and do not constitute what amounts to a shadow government, such as

the group of non-elected, largely unaccountable individuals who led the US into

its catastrophic invasion of Iraq in 2003.

It will therefore be of capital importance for Taiwan that in the months and

years to come, KMT-appointed special advisers are scrutinized and their actions

closely monitored to ensure that they do not endanger the interests of the

nation.

Under a democratic system, accountability is key and the KMT knows this. But

there exists the real possibility that it, or some elements within it, will

substitute the illusion of accountability with the real thing by appointing

government officials who in reality are little more than a smokescreen for

non-elected special advisers whose power will be difficult to monitor. Should

this come about, how much those individuals are paid would be the least of our

worries.

J. Michael Cole is a writer based in Taipei.

Beijing’s

biggest enemy is itself

By Sushil Seth

Monday, May 12, 2008, Page 8

Is there a method to Beijing’s madness regarding the Olympics? Obviously there

is. But if the objective is to make China look good, its ruling oligarchy is

going the wrong way.

They found themselves wrong-footed when the Olympic torch relay became entangled

with the Tibetan human-rights issue. All their heaving and weaving about the

unrest in Tibet failed to convince audiences abroad that it was the work of the

Dalai Lama clique involving some wayward monks.

All this talk of cultural genocide in Tibet, Beijing believes, is a canard

fostered by the Dalai clique to defame China and split it from the “motherland,”

a heinous crime by enemies of the country. It was an overkill, figuratively and

literally speaking, by a regime used to this sort of talk.

Having been caught on the defensive, Beijing decided to go on the offensive.

It is sheer madness to elevate the Olympic torch relay into an issue of

monumental importance to China as if the country’s future depended on it.

China had hoped to formally inaugurate its new status as a superpower through

the Olympic extravaganza, choreographed in Beijing with other countries cast in

a supporting role. It would be the international acknowledgement of China’s new

power, with heads of states making a beeline to pay homage to the star of the

21st century.

But the pesky Tibetans have upset China’s carefully choreographed Olympic drama.

And any talks with the Dalai Lama’s representatives will be a diversionary

tactic to drag on until the Olympics are over.

What is the method in this madness? First, it is enabling the regime to mobilize

Chinese people behind the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) on a highly-charged

issue of national honor of hosting the Olympics — a sort of coming of age party

for China as a great and respected power.

By promoting, projecting and upholding the national honor against hostile

international elements (particularly in the West), the CCP and the nation become

indistinguishable. In other words, the party is the nation and vice versa.

Any voice of dissent and moderation in China is thus silenced. And the regime

finds itself suddenly enjoying a level of legitimacy. And, temporarily, people

forget all its sins of omission and commission.

Such madness of rallying people against a highly charged symbol of national

honor is dangerous. Adolf Hitler did it in 1936, enveloping Germany in an orgy

of self-congratulation. And we know what eventually happened there when

nationalism developed into chauvinism leading to World War II.

It is not suggested that China is necessarily going that way, but to stress the

extreme danger of stoking nationalism that might easily get out of hand.

The danger is not from the Olympics, but from its misuse as the symbol of

national honor and glory.

One sincerely hopes that China’s leaders are aware of the dangerous game they

are playing with nationalism. For instance, such overtly visible use of its

paramilitary blue tracksuits-wearing contingent to provide security for the

Olympics flame simply aggravated the situation in London and Paris, leading to

the charge that they were acting like “thugs.”

And in Australia, during the Olympic torch relay in Canberra, the Chinese

embassy reportedly was involved in putting together a show of support by about

10,000 Chinese in Australia who descended on Canberra in buses from Sydney and

Melbourne.

They went about intimidating, screaming and jostling anyone seen as a Tibetan

supporter. A headline in the Australian newspaper described it as: “Chinese

students bully torch crowds.”

A Sydney Morning Herald reporter said: “It was intimidating to look into the

screaming faces of Chinese supporters who held flags out of passing car windows

and screamed ‘One China’ to Tibetans.”

One Australian woman was quoted as saying that, “It’s pretty insulting that

Australians in their own country need riot police to protect them from foreign

nationals.”

And the irony of China supporters exercising their right of free speech and

peaceful protest (even when it was not so peaceful) in Australia was not lost on

observers and commentators, aware of the fate of the protesters in Tibet or, for

that matter, the 1989 Tiananmen Massacre.

A cartoon in the Australian was biting in its double-edged irony. It shows a

Free Tibet supporter forcefully telling a China supporter: “You’d be shot in

China for demonstrating there.” The China supporter equally forcefully responds:

“I’d be shot in China for not demonstrating here.”

Even more objectionable was the cavalier way in which the Chinese authorities

sought to override Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s public declaration

that China’s track-suited paramilitaries would not have any security role during

the Canberra torch relay.

Rudd’s pledge to uphold Australian law in providing security for the torch was

contested by China till the end.

The point of recapitulating the Olympic torch relay through Canberra is to

highlight Beijing’s highhandedness and arrogance even when the international

event involved, the Olympics, is simply a celebration of international sport.

Imagine China’s volatile reaction if it were an event involving some territorial

issue, with Beijing regarding it as an infringement or violation of its

sovereignty. And imagine further the sort of national mobilization Beijing might

bring about with unpredictable consequences.

Sure, there is a method to China’s madness regarding the national hysteria over

the torch, with the Western world seen as indulging the Dalai Lama’s “nefarious”

activities. It has given the regime a certain level of legitimacy as the

upholder of China’s national interests.But it is a dangerous game the CCP is

playing. To maintain and sustain such legitimacy, it will be required to produce

concrete results to satisfy enhanced national expectations all around.

And that is a Herculean job which even the CCP might not be able to deliver. In

the meantime, the world waits with baited breath to see where China’s ultra

nationalism will take it.

Sushil Seth is a writer based in Australia.