‘No real

freedom in China,’ Cardinal Joseph Zen says

AFP , HONG KONG

Tuesday, Jun 02, 2009, Page 1

The former leader of Hong Kong’s Catholic Church yesterday hit out at Beijing

for its stance over the 1989 pro-democracy demonstrations in Tiananmen Square

and voiced concern for religious freedom.

Cardinal Joseph Zen (陳日君), a staunch democracy advocate and long-time vocal

critic of the Chinese government, said he wanted to see an official

re-examination of the bloody crackdown on student demonstrators 20 years ago

this week.

“I hope they really consider seriously the possibility of a reassessment of the

verdict,” Shanghai-born Zen said in a speech at Hong Kong’s Foreign

Correspondents’ Club, three days before the June 4 anniversary.

“It will not damage anyone, but would be to the advantage of the whole nation,”

he said.

The events of 1989, in which hundreds or possibly thousands died when the army

moved in on the young protesters, remain taboo in China, where the government

blocks any mention of it in the press and on the Internet.

Beijing has refused to change its position that the protests threatened Chinese

Communist Party rule and had to be quelled to maintain economic reforms.

Asked when or if he thought the Chinese government would soften its stance, Zen

said: “Things in China are unpredictable. It may happen tomorrow or still take

20 years.”

Zen, 77, an official adviser to Pope Benedict XVI since his recent retirement,

said he was also deeply concerned for the freedom of the Church in the world’s

most populous country.

“There’s no real freedom in China, I’m sorry to say,” the cardinal said, adding

the state of the Church there was “more close to my heart” than even the

Tiananmen issue.

Academics

call for review of policy that capital punishment deters crime

By Shelley Huang

STAFF REPORTER

Tuesday, Jun 02, 2009, Page 2

|

|

| Chiu Hei-yuan,

convener of the Taiwan Alliance to End the Death Penalty, right, shakes

hands with Birgitt Ory, director of the German Institute Taipei, during

a book launch in Taipei yesterday. PHOTO: CNA |

Academics yesterday urged the government to review its policy

on capital punishment by conducting an in-depth study on whether it discourages

crime.

A panel discussion on the death penalty and its effect on crime rates was held

yesterday as part of a book launch to promote "New Ideology beyond the Pros and

Cons of the Death Penalty," a collection of essays from a seminar organized by

the Taiwan Alliance to End the Death Penalty last November.

“We hope to initiate dialogue on the issue of the death penalty from a rational

point of view,” said Birgitt Ory, director of the German Institute Taipei, which

co-sponsored the publication of the book.

The institute aims to share Germany’s experiences following its abolition of the

death penalty. It also hopes Taiwanese would find “living in a society without

the death penalty is not only a possibility, but also a better choice,” Ory

said.

The book contains essays by four German academics and detailed discussions among

the four and 15 Taiwanese experts who participated in the conference on social

security, prison reform, protection of victims and other issues.

“What is written on paper will be preserved,” Ory said. “We hope to provide

thought-provoking ways of looking at the issue of the death penalty and inspire

readers’ thinking on the subject.”

Panelists said that taking the life of a criminal was not necessarily the best

way to compensate for the loss of the victim.

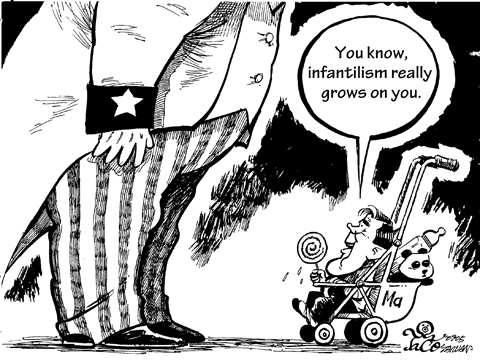

Experts urged President Ma Ying-jeou's (馬英九) administration to set a timeline

for gradually abolishing the death penalty, instead of delaying it until the

next president takes office.

Attorney Nigel Li (李念祖), who is also a board member of the Judicial Reform

Foundation, said that since the legislature on March 31 ratified the Act

Governing Execution of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

(公民與政治權利國際公約及經濟社會文化權利國際公約施行法), Taiwan should re-examine its law on the death

penalty.

Since Taiwan has not executed a death row prisoner in more than four years,

panelists urged the government to perform a statistical analysis on the crime

rate to determine whether the abolishment of death penalty would have any effect

on discouraging crime.

Tiananmen

moms keep memory alive

SILENCE: Two decades later, a

group of mothers is still struggling to make a list of the dead and to overturn

a verdict that the movement was ‘counter-revolutionary’

REUTERS , BEIJING

Tuesday, Jun 02, 2009, Page 6

|

|

| Students share

a laugh with a security guard in Tiananmen Square in Beijing yesterday.

Twenty years after their forebears stood up for political reform with

the 1989 pro-democracy demonstrations in the square and the resulting

bloody crackdown, students today shrug that off with a mixture of

ignorance, political apathy and different priorities. PHOTO: AFP |

Twenty years after her teenage son was shot by troops near Tiananmen

Square in Beijing, Zhang Xianling (張先玲) is still trying to work out how many

others died with him.

Beijing’s refusal to release an official figure for the number killed on June 4,

1989, is symbolic of its larger silence about the crackdown on student

protesters.

China’s economy is now the third largest in the world, an achievement that would

have been unthinkable during the impoverished 1980s. But political reform has

stalled, with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) quick to stamp out any perceived

challenge.

“China is on the road to democracy and the rule of law, but we don’t know how

long that road will be ... Before, I thought I would see the day, now I am not

so sure,” Zhang said in an interview in her living room, filled with books and

her husband’s musical instruments.

“Now the economy is more developed. A lot of people just chase economic

advancement, and don’t worry about politics,” she said.

Zhang’s son, Wang Nan (王楠), was a cheerful, bespectacled 19-year-old when he

left a note on the night of June 3 to say he was going to join friends on

Tiananmen Square.

It took 10 days before his disinterred body was returned to his parents. His

glasses were still on his face.

Zhang founded Tiananmen Mothers with another woman, Ding Zilin (丁子霖), whose

17-year-old son was also killed. The group is trying to make a list of the dead

and urge for a reassessment of the verdict that the movement was a

“counter-revolutionary” plot.

They recently confirmed one more name, bringing their list of victims to 195.

Zhang believes they have only identified about one-tenth of those killed.

“Our greatest hope is to be able to openly say it was wrong for the army to fire

on people. Civil society should be able to participate in an investigation,”

Zhang said.

Their quest is impeded by police surveillance, the mistrust of families of the

dead and the demolition of Beijing’s old alleyways, which has scattered

neighbors and made families harder to track down.

The group issued a statement in the run-up to the 20th anniversary of the

crackdown calling for an investigation, compensation and prosecution of those

responsible.

After 20 years, the rush for wealth has become a bigger priority for most

Chinese than dwelling on the past, or even pressing for greater freedoms,

reformers like Zhang acknowledge.

But recent events have spawned a new generation of activist parents, seeking

explanations for the deaths of thousands of schoolchildren during a devastating

earthquake in Sichuan Province last year, or seeking compensation for infants

who died or were sickened after drinking contaminated milk powder.

Like the Tiananmen Mothers, those parents are being followed, monitored and

detained, showing the CCP is still nervous their activism could threaten its

hold on power. June 4 is taboo for the Chinese media and on Sunday, the CNN feed

in Beijing was cut when the Tiananmen movement was mentioned.

Six months before the anniversary, a group of Chinese intellectuals released

“Charter 08,” calling for freedom of speech and multiparty elections, but such

Tiananmen-era calls for reform are few and far between.

Memoirs of purged CCP chief Zhao Ziyang (趙紫陽), in which he denies the 1989

student movement was a counter-revolutionary plot, sold out when they were

published in Hong Kong last month.

“History has stopped at this point. Reform has stalled,” Bao Tong (鮑彤), Zhao’s

aide and the highest-ranking official jailed in the crackdown, said from his

home where he is monitored by police.

“We can’t explain this to our own students, and people overseas probably

understand even less. We need the government to open up and truly discuss it,”

Bao said.

Zhang says her long fight to shed light on her son’s death taught her the duties

of citizenship.

“After 20 years, my opinion hasn’t changed. The students were protesting against

corruption ... 20 years later, we can see they were right,” Zhang said.

“Corruption is everywhere. The students were prescient,” she said.

Wang Dan

has no regrets over his role in 1989

AFP , BEIJING

Tuesday, Jun 02, 2009, Page 6

Wang Dan (王丹), who once topped the Chinese government’s most wanted list of

leaders of the 1989 Tiananmen democracy movement, remains fiercely proud of his

role, despite years in jail and exile.

“We lost a lot but we gained a lot too ... I’m proud every time I think about

it,” Wang said in an interview from Taiwan.

Twenty years on he has no regrets over the tumultuous period that transformed

him from a college student to a counter-revolutionary.

Along with other student leaders like Chai Ling (柴玲) and Wu’er Kaixi (吾爾開希),

Wang led six weeks of peaceful protests from makeshift tents on Tiananmen

Square, turning the movement into the biggest threat ever to Chinese Communist

Party (CCP) rule.

“We did not make sufficient preparation at the time,” Wang said of his eventual

capture and nearly seven years of imprisonment.

In 1998 he was expelled to the US following an international campaign for his

release.

He graduated with a doctorate in history from Harvard University last year and

currently is a senior associate member of Oxford University, where he continues

his fight to bring democracy to China.

A photo of Wang in Tiananmen Square epitomizes youth in revolt. Microphone in

hand, long floppy hair brushed away from big, round glasses, Wang thoughtfully

harangues the crowd with a tense look on his face. At the time he was 20 years

old.

“We are going to take back the powers of democracy and freedom from the hands of

that gang of old men who have grabbed those powers away from us,” Wang said in

his first speech at the end of April 1989.

“What was the most memorable for me was the demonstration on April 27,” Wang

said in an interview conducted 20 years later.

“There were banners everywhere. This was the first unauthorized political

demonstration in the People’s Republic of China ... the Chinese people had begun

to speak with their own voice,” he said.

An editorial in the People’s Daily a day earlier triggered the protest after it

called the initial days of unrest “a well planned plot ... to throw the country

into turmoil” and “reject the Communist Party and the socialist system.”

Defying police orders, more than 50,000 Beijing students walked from the

university district to Tiananmen Square in an orderly and peaceful march that

elicited wide support from the local population.

There was a sense of euphoria, as students felt victory could be within reach.

“There were indeed many differences in opinion among students, but obviously

that was not the cause for the massacre,” Wang said.

“It was the differences in opinion among the Chinese Communist Party leadership.

As long as the government insisted on suppression, it would not have mattered

what strategy or tactics the students adopted, the result would be the same,”

Wang said.

Wang said that China’s leaders today “are a lot more conservative” than leaders

in 1989 like Hu Yaobang (胡耀邦) and Zhao Ziyang (趙紫陽), the two top party leaders

who were ousted in 1987 and 1989 respectively for being too soft on student

protests.

“Today’s leaders no longer have any will to change the way the Chinese Communist

Party governs,” Wang said.

“Of course we are facing more difficulties than in 1989,” he said. “Economic

development has distracted people’s attention and the international environment

has changed.”

This has not prevented Wang from maintaining contact with many of the veterans

of the 1989 movement, including those in China.

“The government has less and less control over the people, a civil society is

emerging with the help of the Internet,” he said.

And what has he himself learned from the history-changing events 20 years ago?

“I learned to be patient in waiting, being optimistic while facing the

difficulties,” Wang said.

“I am optimistic on returning to China. I think it will come soon,” he said.